CHORA PARK 2018

- wp_7961204

- 0

- on Jan 20, 2019

Elio Franzini

The political space of beauty

Beauty, says Paul Valéry, is not to be considered a “pure notion”, even if it is one that has been fundamental in the history of western spirituality, and determined a metaphysical thought that is the foundation of philosophy. To summarize, and with all the risks that summarizing implies, Plato does exactly what according to Valéry should not be done to separate the Beautiful from beautiful things.

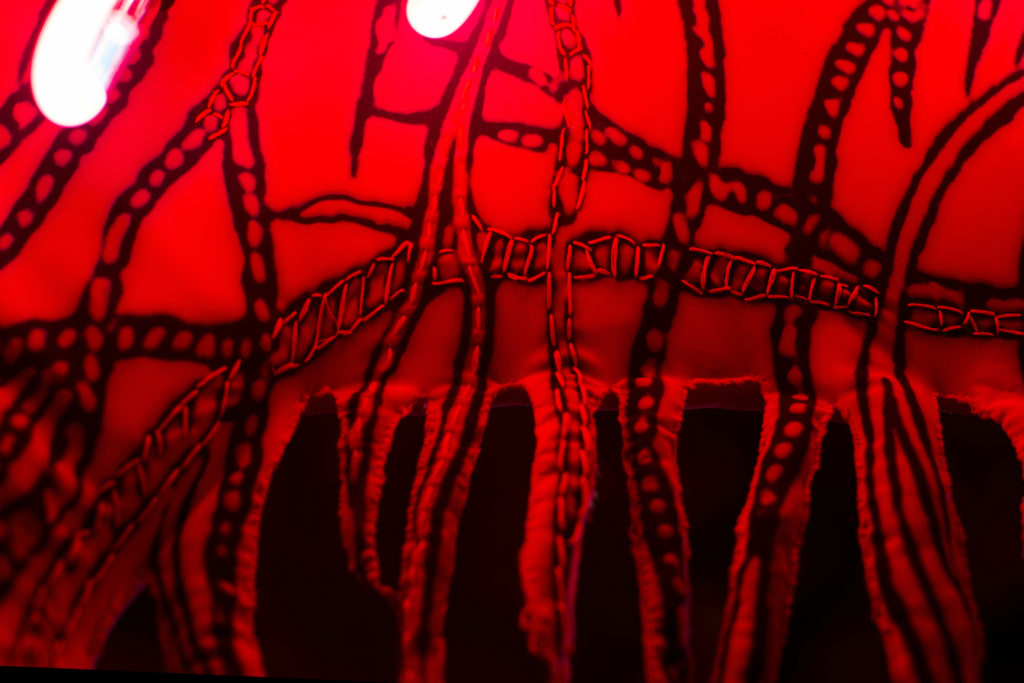

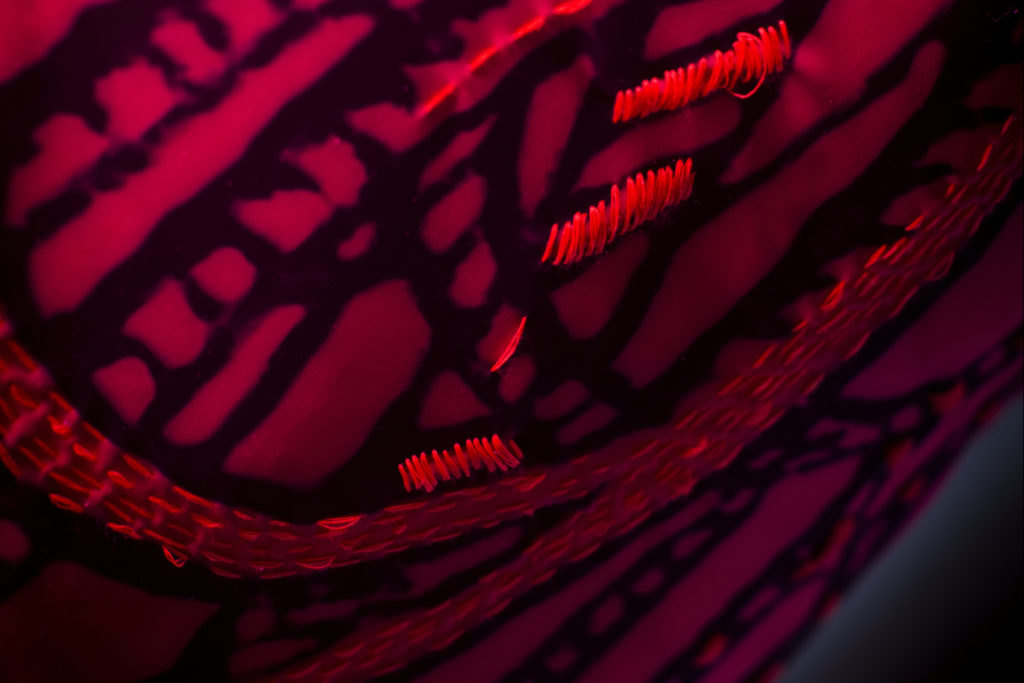

Marina Gasparini’s work, instead, teaches us to situate beauty in space, in what the Greeks called, using an ambiguous term, chora, i.e. the place – the uncertain place – where the polis, the city, is inscribed. A work that is an environment where, as in the blood, through blood-like threads, microcosm and macrocosm blend. Meaning or beauty or art can reside in the heavens as “idea” that can’t be perceived by the senses, but they can also be “aesthetic” idea that is fragmented in things, or in our body – in between Copernicus and Vesalius. At the same time, nothing keeps us from searching for, and possibly finding the universal in the particular, thereby creating the happy synthesis we see in this installation. Here beauty does not reside only in the metaphysical heavens precisely because its “ideality” becomes political, chora, embodying itself in “objects” destined to occupy public and social spaces.

In this work we find a genuinely “political” vision of public space, which is presented through institutionalized aesthetic characters. In beauty there needs to be a “superior” principle, that of symmetry, which consists in a harmonious agreement among the parts of the work, and in their correspondence with the configuration of the whole. In the construction of a beautiful object there is also the need for order, which derives from a correct disposition of the parts, and which translates into eurythmics, symmetry, propriety and distribution. The goal is venustas, beauty, arranged in a skilful game of modularity. The patterns built up here generate a “mixed” form that constitutes the open unification of different concepts, different ways of conceiving the polis. Beauty was, and is, a way of determining a sense of a form that is not closed into itself. Rather, it always presents itself as a “referring structure” in search of an organic relationship between the visible and the invisible, between public and private. Above all, it can foster communication among subjects, as well as the formulation of judgments able to connect the spiritual and the corporeal on the social plane. Marina Gasparini’s installation teaches us that art, to use an expression of Pavel Florenskij, requires a polycentricity of representation: art is not a distant idea, but a way to better observe, describe and reproduce the quality of the events of the world, the chora that contains the polis we inhabit.

The era of the transitory, as Karl Löwith calls our modernity, must learn to spin the red threads that weave a new chora, in all its ambiguity, a new environment that is conscious of humanity’s wavering between order and chaos, and of its continually threatened stability, but where the operations of nature and of humanity are renewed in a Faustian spirit. Faust is now the image of what may be the political function of beauty in our time: the acceptance of polyvalence and plurality. This function is infinitely multiplied; its destiny, and its torment, is to start again without ever exhausting either the enduring or the possible. Thus, it synthesizes a journey that includes the aporias of modernity, searching for their measure and for a new spirit to interpret them by. It discovers the red thread of a modernity, where dialogue is possible: dialogue between knowledge and power, between self and other, between the project and its crisis, between ideas of space that are shared and yet distant. Its time does not absorb the dialoguing elements in static metaphysics or in a circle turning back on itself as a dream of paganism. Rather, it sets the instant in motion and shows the constructive possibility of multiplicity, the desire for unity within it, and the stability and free will of a form brought into existence by an aporetic movement.

Chora, therefore, indicates a political dialectics of beauty, a polyphonic dialectics, where no one principle overpowers the others. It shows a way of seeing space as a “system of references” that can be viewed “at a distance”, almost as though objectified by the spiritual efforts of the observer, and which at the same time is lived in, so that places become descriptions of paradigms in search of the conceptual values of spatiality.

And so we come to a conclusion that takes us back to where we began, to the primary motor of this installation by Marina Gasparini: in short to Plato, to a passage from his Gorgias in which Callicles is admonished because he fails to take into account that heaven and earth, the gods and men, are linked in a community of friendship and moderation. Callicles does not take this into account because he forgets the geometrical equality, that is to say an idea of kosmos – perhaps the only idea to which, in its polyvalence, it is possible to reconnect the idea of beauty without losing ourselves in its historical mutability and fallibility.

The question, then, is how to recover a political conception of space, according to the model offered by the Gorgias, considering that the organization of space is only one aspect of a more general effort to interpret and represent the human world.

What this kosmos is today is hard to say or define or perhaps even conceive; but all this have to make beauty become a truly “civil” space and not an abstract or subjective ideal. As we observed at the beginning, Valéry ironizes about the philosophical desire to define beauty, separating the beautiful from beautiful things, from the spaces where it appears, from the “cities” it lives in. Valéry wants to distinguish beauty from the rhetoric that invades it, banishing it from our political space. Yet if we observe the history of beauty from ancient times to the birth of modernity, we can find a path to follow to make beauty “political” and not just abstractly philosophical, by situating it, as is done here, in a chora.

But this also means understanding that beauty “comes from below”: it knows ugliness and deformation. It is not only a luminous, aesthetically pleasing and self-referential image; it is not only the pleasure of forms. Rather, it is a “grace”, an offering, a sign of openness to the world, conscious of the hardships and potential tragedy of the finite that inhabit it with their disagreements and their dialoguing values. It is therefore the ideal structure, the general name for the project of a journey that finds its own fulfilment in the complex growth of cultural, mythical and symbolical forms.

Chora Park

2018

Installation

3 textile sculptures 140×230 cm

Neon light, fabric, embroidery

and

13 elements diameters from 10 to 70 cm

neon light, metal

Elio Franzini

Lo spazio politico della bellezza

La bellezza, sostiene Paul Valéry, non può essere considerata una “nozione pura”, anche se tale nozione è stata essenziale nel divenire della spiritualità occidentale e ha segnato una metafisica che è alla base del pensiero filosofico. Platone, volendo sintetizzare, e con tutti i rischi della sintesi, opera proprio ciò che, a parere di Valéry, non andrebbe fatto, cioè separa il Bello dalle cose belle.

Il lavoro di Marina Gasparini insegna invece a ricollocare la bellezza nello spazio, in quel termine ambiguo che i greci chiamavano chora, che è il luogo – il luogo incerto – in cui si inscrive la polis, la città. Ambiente in cui si fondono, come nel sangue, attraverso fili che sembrano sangue, microcosmo e macrocosmo. Il senso, la bellezza, l’arte, può essere nei cieli, come “idea” non sensibile, ma può anche essere idea “estetica”, che si frantuma nelle cose, nel nostro stesso corpo – tra Copernico e Vesalio. Al tempo stesso, nulla vieta di cercare, ed eventualmente trovare, l’universale nel particolare, operando, come in questa installazione, una sintesi felice. Qui la bellezza non è soltanto nei cieli della metafisica: e se ciò non accade è proprio perché la sua “idealità” diventa politica, chora, incarnandosi in “oggetti” destinati a occupare spazi pubblici e sociali.

Vi è qui, in questo lavoro, una vera e propria visione “politica” dello spazio pubblico, che si presenta attraverso istituzionalizzati caratteri estetici. Vi deve così essere, nel bello, un principio “superiore”, che è quello della simmetria, che consiste nell’accordo armonico tra loro delle parti dell’opera e nella loro corrispondenza con la configurazione complessiva. Vi è inoltre nella costruzione di un oggetto bello l’esigenza di ordine, che deriva da una corretta disposizione delle parti, che si traduce in euritmia, simmetria, convenienza e distribuzione. Il fine è la venustas, cioè la bellezza, che si compone in un sapiente gioco modulare. I disegni che qui si costruiscono generano una forma “mista” che è unificazione aperta di concetti diversi, di differenti modi di concepire la polis. Il bello è stato, ed è, un modo per determinare il senso di una forma che non si chiude in se stessa, ma sempre si pone come “struttura di rinvio”, alla ricerca di una relazione organica tra visibile e invisibile, tra pubblico e privato. In grado, in primo luogo, di favorire la comunicazione tra i soggetti, l’articolazione di giudizi capaci di connettere sul piano sociale lo spirituale e il corporeo. L’installazione di Marina Gasparini insegna che l’arte, per usare un’espressione di Pavel Florenskij, esige una policentricità della rappresentazione: l’arte non è una idea lontana, ma un modo per meglio osservare, descrivere, riprodurre la qualità degli eventi del mondo, la chora che contiene la polis che abitiamo.

L’epoca del provvisorio, come Karl Löwith chiama la nostra modernità, deve saper creare i fili rossi che costruiscono, in tutta la sua ambiguità, una nuova chora, un nuovo ambiente, consapevole dell’oscillare dell’uomo fra ordine e caos, in una stabilità sempre minacciata, ma all’interno della quale si rinnova, con spirito faustiano, il fare della natura e quello dell’uomo. Faust è ora l’immagine di quel che forse può essere la funzione politica della bellezza oggi, che è quella di accettare la polivalenza e la pluralità: è qualcosa infinitamente moltiplicato il cui destino, e il cui tormento, è quello di ricominciare senza mai esaurire né la durata né il possibile. In questo modo sintetizza in sé un percorso che raccoglie le aporie della modernità, alla ricerca di una loro misura, di uno spirito nuovo che le interpreti. Scopre il filo rosso di una modernità come possibilità di dialogo, dialogo tra il sapere e il potere, tra il medesimo e l’altro, tra il progetto e la sua crisi, tra concezioni dello spazio comuni e pur distanti: il suo tempo non assorbe in sé, nella staticità metafisica o in un circolo che ritorna su se stesso in un sogno paganeggiante, gli elementi in dialogo, bensì pone in movimento l’istante, mostra la possibilità costruttiva del molteplice, il desiderio di unità che è in esso, la stabilità e l’arbitrio di una forma posta in essere da un movimento aporetico.

Chora indica dunque una dialettica politica della bellezza, una dialettica polifonica, dove nessun principio prevarica sugli altri: mostra uno sguardo sullo spazio che lo disegna come un “sistema di riferimenti”, che può essere considerato “a distanza”, quasi oggettivato dagli sforzi spirituali di chi osserva e, al tempo stesso, vissuto, in modo che i luoghi siano descrizione di alcuni paradigmi alla ricerca dei valori concettuali della spazialità.

Ci si può allora avviare a una conclusione che riporti all’inizio, al motore primo di questa installazione di Marina Gasparini, cioè a Platone, in un passo del Gorgia, in cui si rimprovera Callicle perché non tiene conto che il cielo e la terra, gli dèi e gli uomini sono legati tra loro in una comunità fatta di amicizia e moderazione. Callicle non ne tiene conto perché dimentica l’uguaglianza geometrica, ovvero un’idea di kosmos – forse l’unica a cui, nella sua polivalenza, si possa ricondurre l’idea di bellezza senza perdersi nella sua mutevolezza, e fallibilità, storica.

Si tratta così di recuperare proprio una concezione politica dello spazio, sul modello offerto dal Gorgia: l’organizzazione dello spazio è soltanto un aspetto di uno sforzo più generale per interpretare e rappresentare il mondo umano.

Che cosa sia oggi tale kosmos è difficile da dire, da definire, forse anche solo da pensare: il che però deve rendere la bellezza uno spazio davvero “civile”, e non un ideale astratto o soggettivo. Valéry, come già si è accennato all’avvio, ironizza sulla volontà filosofica di definire la bellezza, separando il bello dalle cose belle, separandolo dagli spazi in cui appare, dalle “città” in cui vive. Valéry vuole scindere la bellezza dalla retorica che la invade, escludendola dal nostro spazio politico. Quando, invece, se guardiamo la storia della bellezza dall’antichità agli albori della modernità, vediamo una strada da recuperare, quella proprio di rendere la bellezza “politica” e non solo astrattamente filosofica, inserendola, come qui accade, in una chora.

Ma ciò significa anche comprendere che la bellezza “parte dal basso”, conosce il brutto e la deformazione, e non è soltanto immagine splendente, estetistica e autoreferenziale. Non è soltanto il piacere delle forme, bensì una “grazia”, un’offerta, cioè un segno di disponibilità nei confronti del mondo, consapevole del travaglio e della potenziale tragicità del finito che la attraversano con i loro dissidi, con scale di valori tra loro in dialogo. È quindi la struttura ideale, il nome generale di un percorso progettuale che trova i suoi specifici riempimenti nel divenire complesso di forme culturali, mitiche, simboliche.

Elio Franzini

Professore di Estetica e Rettore dell’Università di Milano

Membro del Comitato Scientifico della Fondazione Collegio San Carlo

CHORA PARK, TRA FAVOLE E REALTA’

video by Sofia Ye

.

Catalogue Chora Park download

Curator: Antonella Battilani

Photos by STUDIO CENTRO 29, Modena,

Coordinator : Gabriele Pollastri

Chora Park