IL DENARO è UN BENE COMUNE 2014

- wp_7961204

- 0

- on Aug 13, 2017

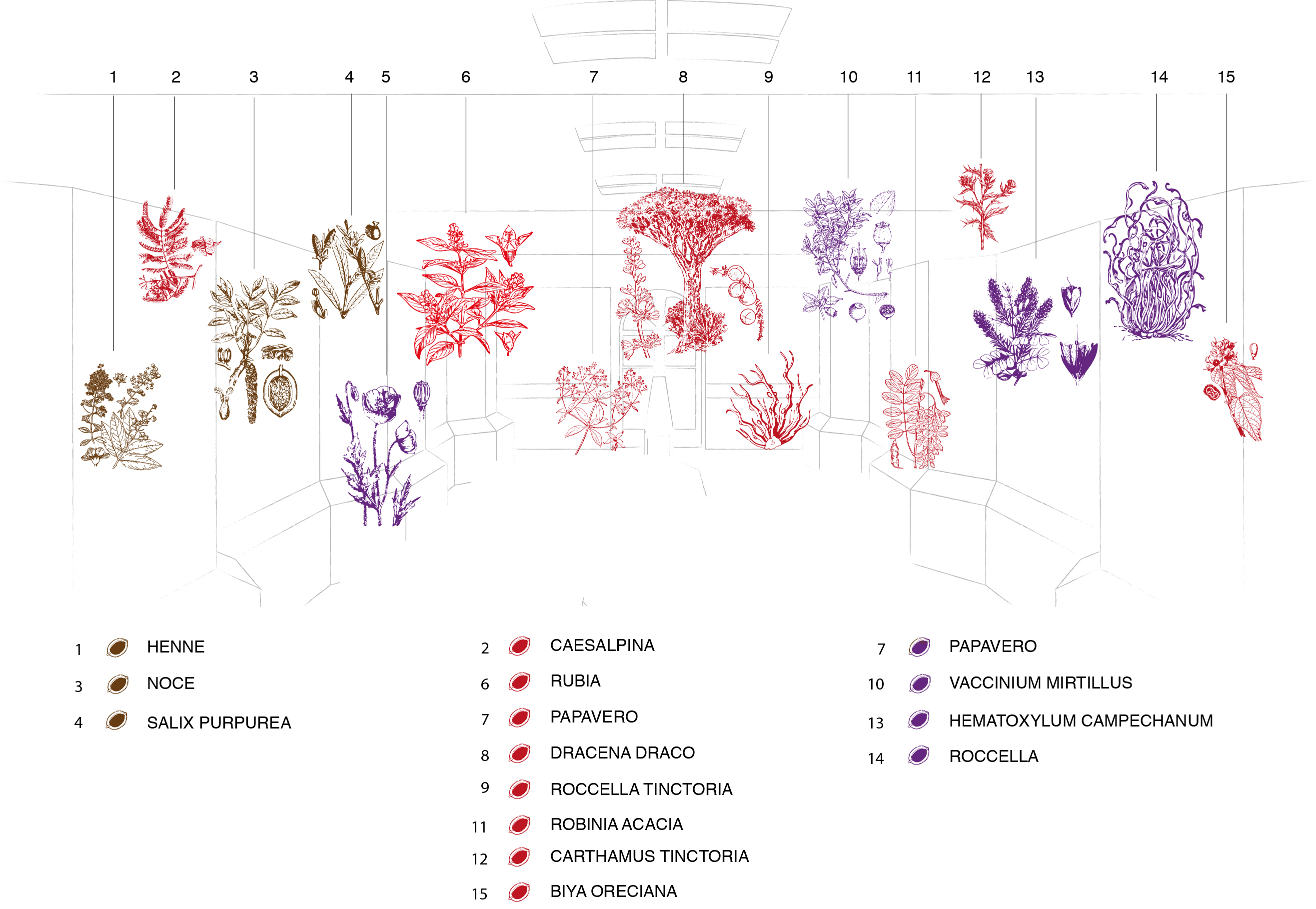

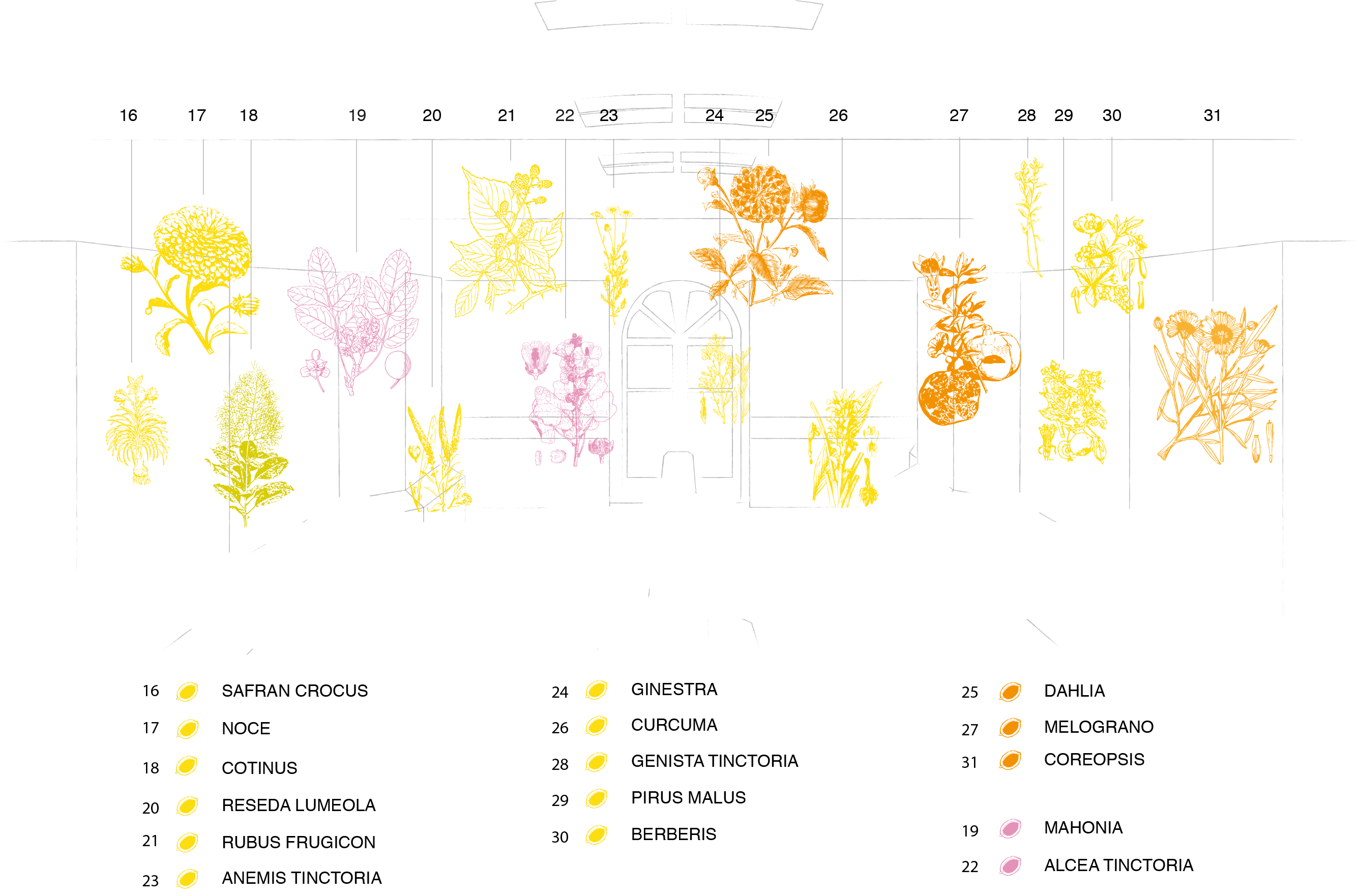

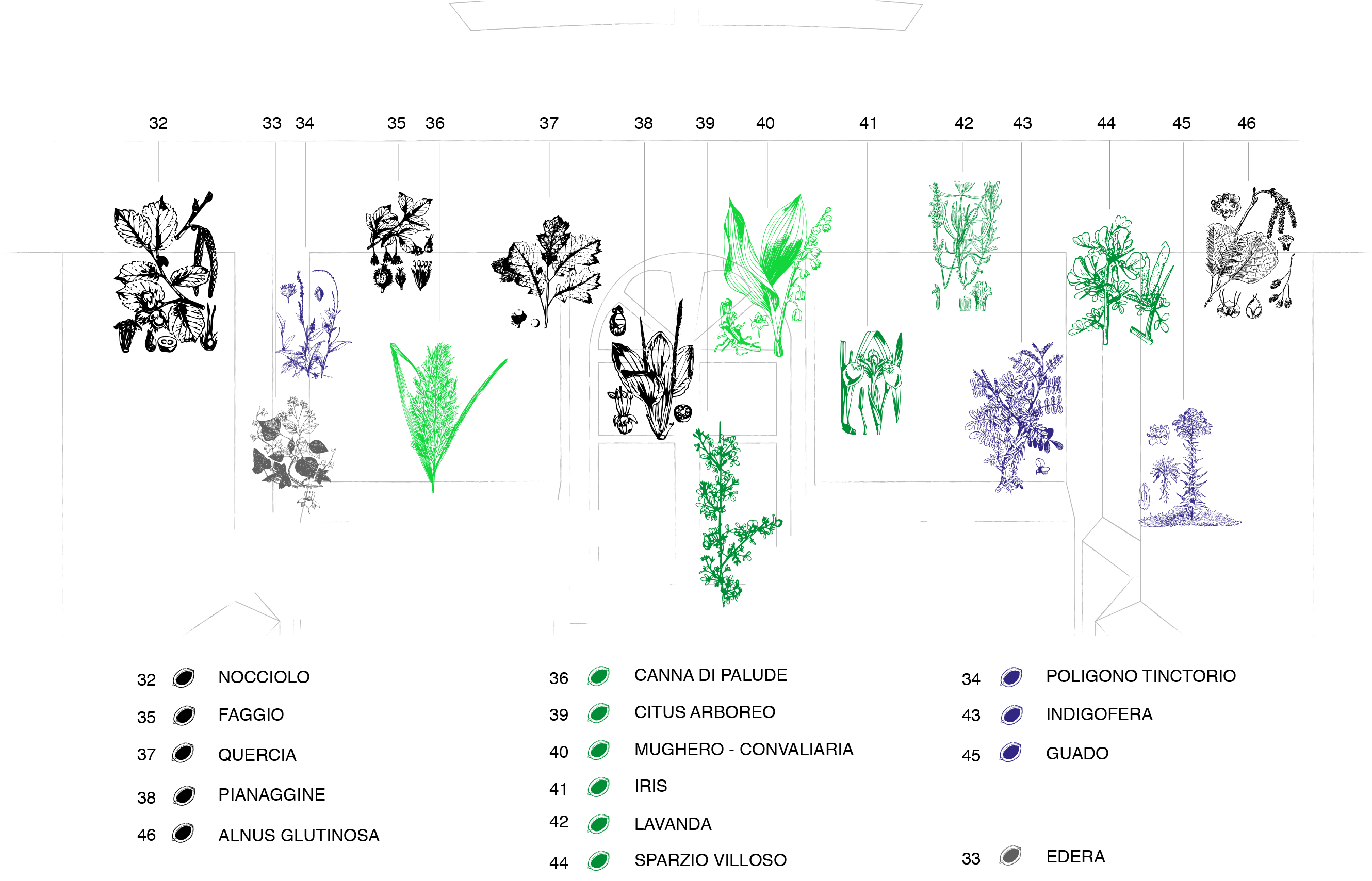

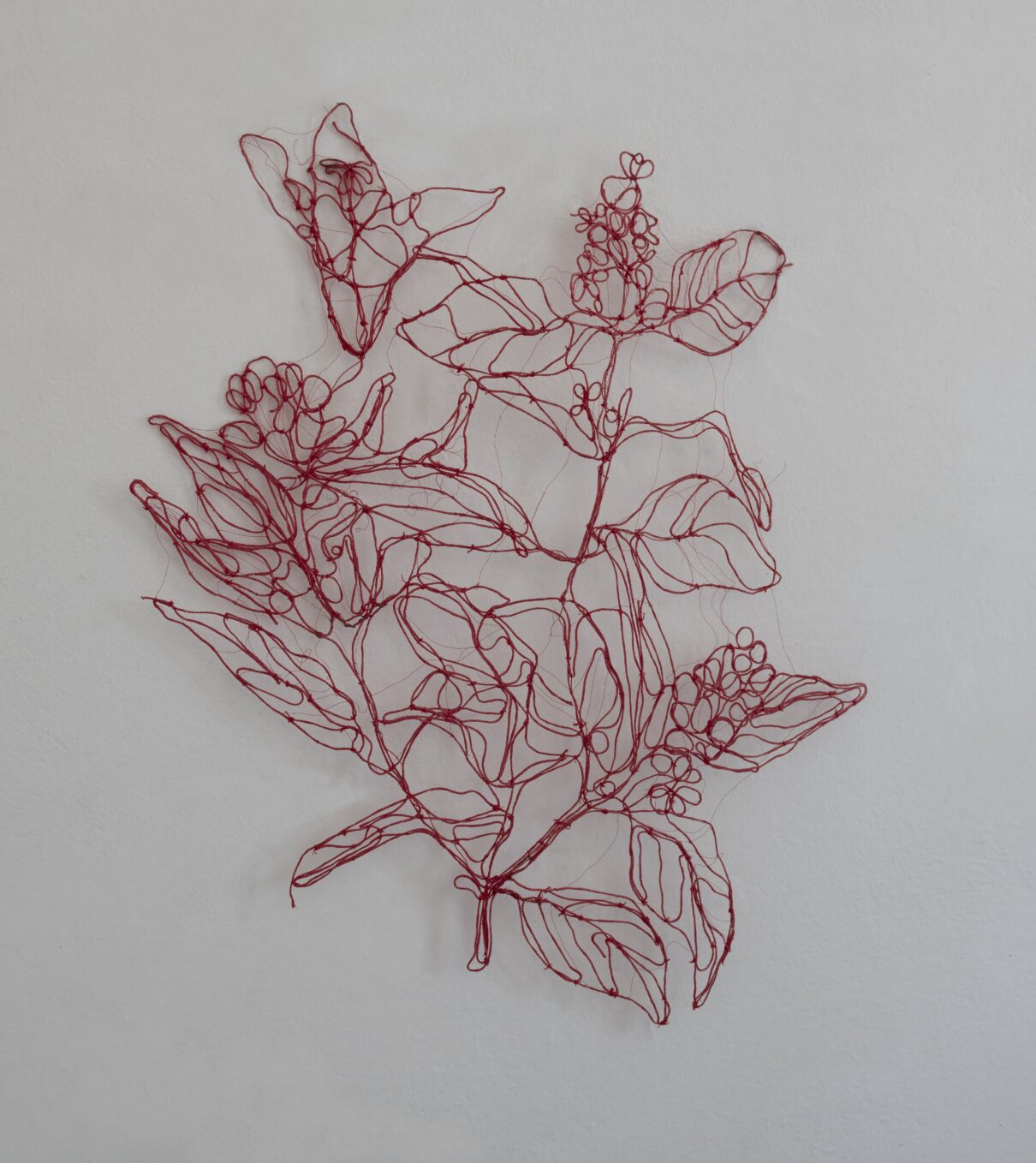

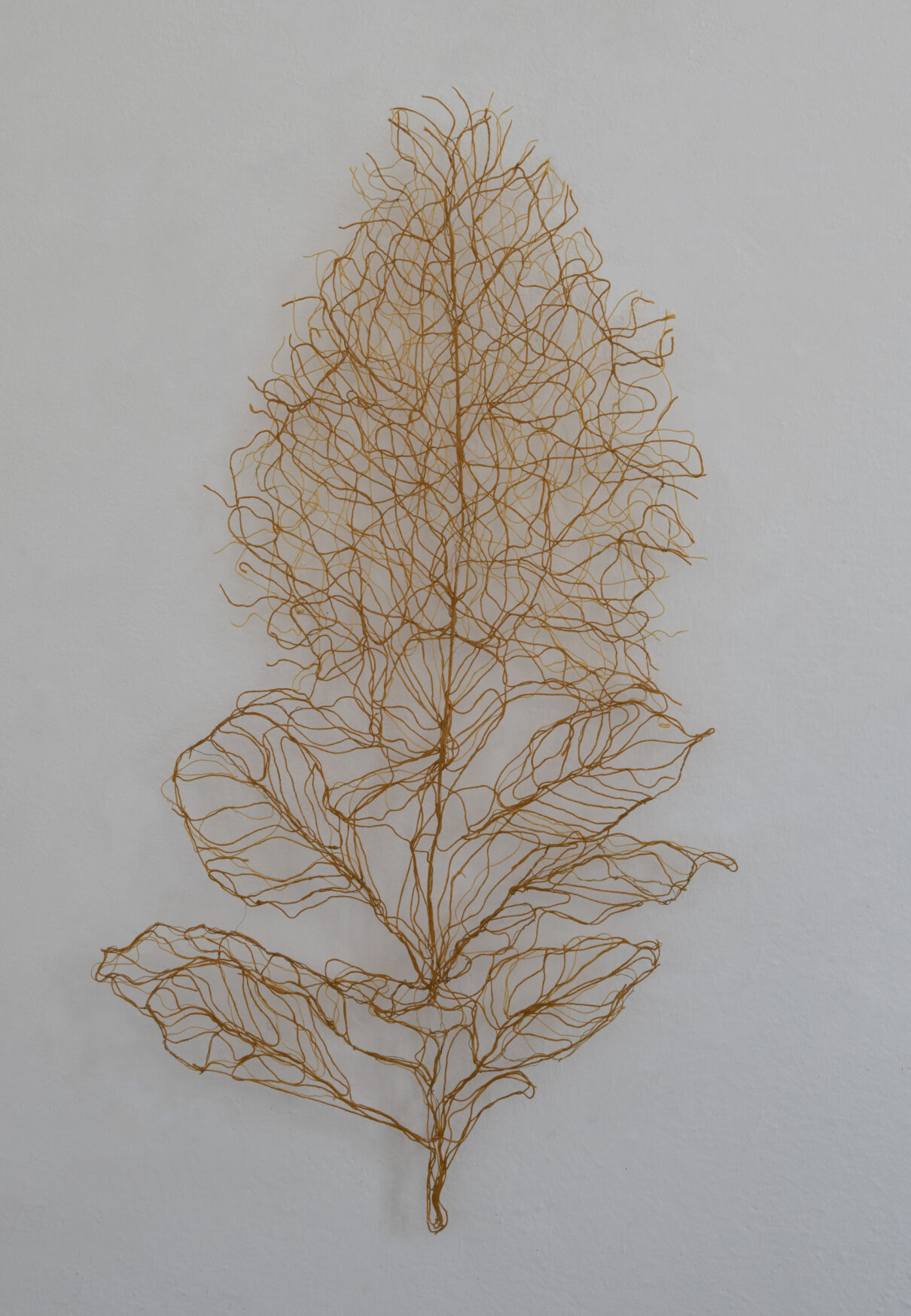

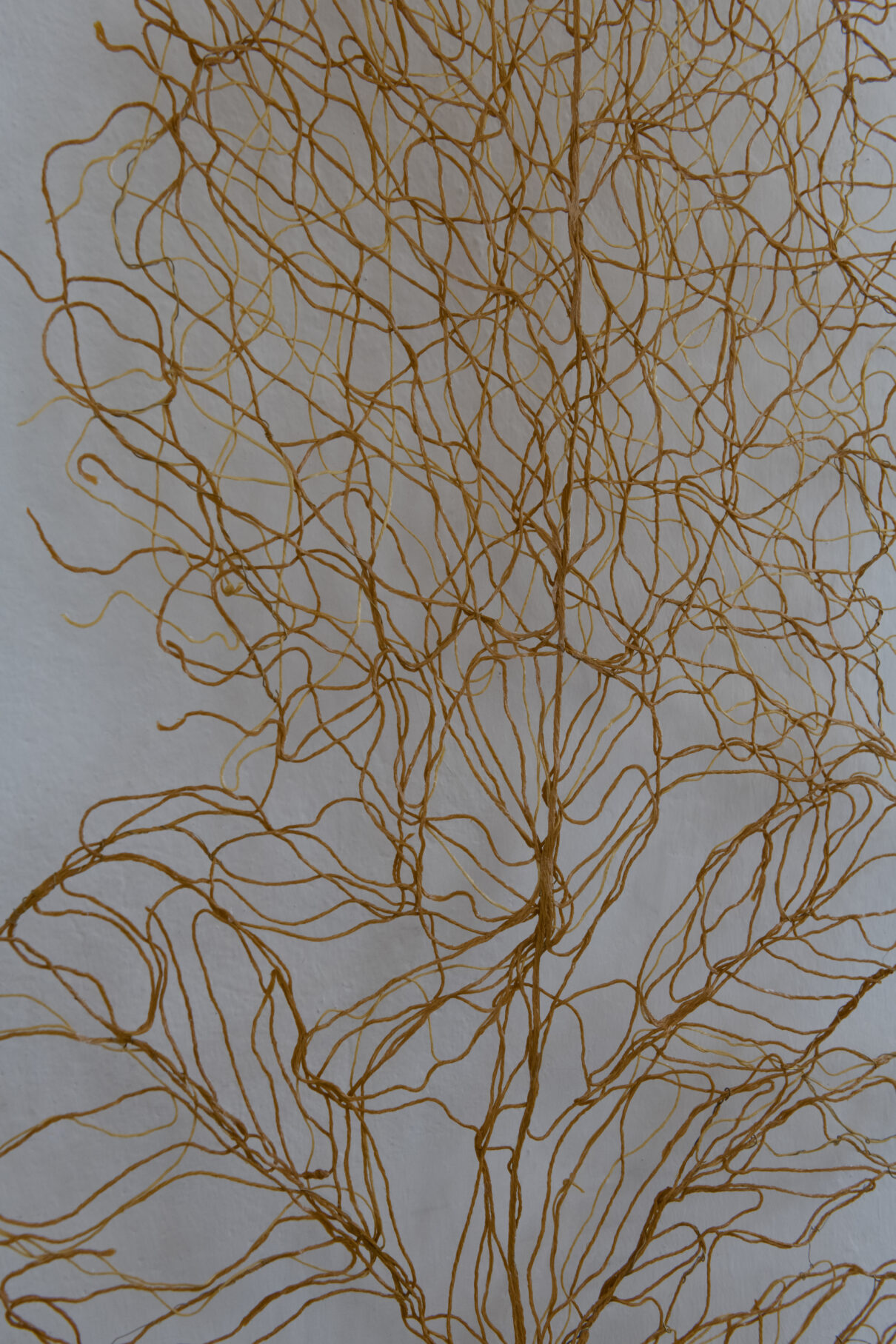

Ancora una volta, dopo Intrecci d’arte al museo nel 2001 e La realtà non è forte di Sabrina Mezzaqui nel 2010, la Sala Gandini del Museo Civico d’Arte di Modena ospita un’installazione che dialoga con la collezione di frammenti tessili donata nel 1884 dal conte Luigi Alberto Gandini e composta da migliaia di campioni tra tessuti, merletti, ricami e galloni. E in questo caso il dialogo è davvero serrato perché al centro della riflessione di Marina Gasparini vi è il tema del rapporto tra arte tessile ed economia, evidenziato dall’epigrafe dipinta al di sopra di una delle porte della sala per volontà dello stesso collezionista e donatore, Dall’arte della lana e della seta l’Italia ebbe ricchezza lustro e civiltà. Un’affermazione, questa, che condensa in sé il significato stesso della collezione, formata a supporto degli studi di storia del costume che tanto interessarono Gandini, ma anche come immenso repertorio di modelli per l’industria tessile che nell’Italia post-unitaria si intendeva rilanciare su base industriale. Rispetto al testo dell’epigrafe fungono ora da cassa di risonanza, all’interno delle grandi vetrine ottocentesche progettate dal collezionista, le frasi realizzate dall’artista con il filo, elemento primario dell’arte tessile ma anche metafora dell’attività creativa dell’uomo che si esplica nel riflettere e nel filosofare, come evidenzia Francesca Rigotti nella sua lettura filosofica del lavoro dell’artista. Propongono passaggi del pensiero economico e filosofico tratti da noti pensatori, quali Bernardo Davanzati, John Stuart Mill, i coniugi Marshall e Vandana Shiva mettono in risalto l’intima correlazione tra natura, ricchezza e bene comune. Dalla natura provengono anche le piante dalle quali anticamente venivano estratte diverse tinture per filati, piante che Marina Gasparini ha riprodotto con precisione botanica attraverso vere e proprie sculture in filo che ha poi appeso come una selva di mangrovie fluttuanti alle catene che attraversano la volta della sala. Un’efficace lettura in chiave critica dell’installazione ce la fornisce comunque più avanti Marco Pierini.

Vorrei invece soffermarmi sulla tecnica utilizzata dall’artista per creare queste sculture, appositamente pensate e realizzate per la Sala Gandini, una tecnica in fondo abbastanza semplice: un filato capace di creare forme complesse seguendo un disegno preventivamente tracciato su supporti viene infine appositamente trattato e diventa, appunto, scultura. Proprio questa relativa semplicità la rende adatta all’organizzazione di un workshop rivolto alle famiglie. In occasione dell’inaugurazione della mostra si è quindi pensato di realizzare un laboratorio condotto da Marina Gasparini che consentirà ai partecipanti di realizzare un disegno tessile floreale. L’esperienza che l’artista propone a Modena ha comunque una dimensione internazionale che ci pare importante sottolineare, perché è già stata sperimentata con successo lo scorso anno a Oulu in Finlandia, presso il Dipartimento educativo dell’Oulun Taidemuseo e prossimamente verrà proposta anche in Illinois, al Civic Art Center di Galensburg. L’inaugurazione della mostra, che avviene in occasione della Giornata del contemporaneo 2014, fornisce anche l’occasione per presentare gli atti del convegno internazionale di studi Antiche trame, nuovi intrecci. Conoscere e comunicare le collezioni tessili, organizzato dal Museo Civico d’Arte nel novembre 2010, in occasione del riallestimento completo dell’intera raccolta in collaborazione con l’Istituto Beni Culturali e Naturali della Regione Emilia-Romagna, che li pubblica ora nella propria collana “Materiali e ricerche” e una linea di oggetti ispirati ad un tessuto rinascimentale della collezione Gandini e realizzata dallo studio milanese di industrial design Davide Montanaro nell’ambito del progetto Nutrire l’arte collegato a Expo 2015. Tanto quest’ultima, quanto la proposta espositiva di Marina Gasparini, col workshop collegato, ci pare forniscano nuove concrete dimostrazioni di come una raccolta di antichi tessuti possa ancora oggi sollecitare la creatività artistica, stimolando un museo come il nostro a ricercare sempre nuove occasioni di dialogo con la contemporaneità.

Francesca Piccinini

Direttrice Museo Civico d’Arte

Once again, after Intrecci d’arte al museo in 2001 and La realtà non è forte by Sabrina Mezzaqui in 2010, the Sala Gandini at the Museo Civico d’Arte in Modena hosts another textile installation which dialogues which the collection of textile fragments, donated in 1884 by Count Luigi Alberto Gandini and made up of thousands of samples, including fabrics, lace, embroidery and trimmings. And in this case, the dialogue really is face-to-face, for at the centre of the reflection offered by Marina Gasparini there lies the relationship between textile art and economics, as highlighted by the epigraph painted above one of the entrances to the room, as desired by the collector and donator himself, reading Dall’arte della lana e della seta l’Italia ebbe ricchezza lustro e civiltà (From the art of wool and silk, Italy gained wealth, lustre and civilisation). This is a statement that sums up the very sense of the collection, put together to back up the studies into the history of customs which Gandini was so interested in, but also as an immense repertoire of models for the textile industry which in post-unification Italy we trying to re-launch on an industrial footing. Inside the great 19th-century vitrines, designed by the collector himself, the words of the epigraph are echoed by the sentences spelled out by the artist using thread, the primary building block of textile art, but also a metaphor of the creative activities of man, expressed through reflecting and philosophising, as Francesca Rigotti underlines in her philosophical reading of the artist’s work. The words feature the economic and philosophical ideas of well-known thinkers, such as Bernardo Davanzati, John Stuart Mill, the couple Marshall and Vandana Shiva, highlighting the close relationship between nature, wealth and the common good. Nature is also the source of the plants from which, traditionally, various yarn dyes were extracted, and Marina Gasparini reproduces these plants using botanical precision with her thread sculptures, set out like a mangrove forest, hanging from the chains across the vault of the room. All all-round critical reading of the installation is then provided by Marco Pierini.

Instead, I would like to focus on the technique deployed by the artist to create these sculptures, designed and created especially for the Sala Gandini. This technique is really rather simple: a yarn capable of creating complex forms, following a design previously drawn onto a support which is then treated so as to become a real sculpture. And it is this relative simplicity which makes it so suitable to a workshop for families. On the occasion of the opening of the exhibition, the idea was therefore to hold a workshop led by Marina Gasparini herself, allowing participants to produce their own floral textile design. The experience that Marina Gasparini will propose in Modena does however have an international dimension to it which should be pointed out, insofar as it was already staged with great success last year in Oulu in Finland, at the Education Department of the Oulu Museum of Art, and shortly after also in Illinois, at the Civic Art Center of Galesburg. The opening of the exhibition, which will take place to mark the 2014 Contemporary Arts Day, also provides the opportunity to present the proce-edings of the international study conference Antiche trame, nuovi intrecci. Conoscere e comunicare le collezioni tessili, organised by the Museo Civico d’Arte in November 2010 on the occasion of the complete restructuring of the entire collection, in collaboration with the Institute of Cultural and Natural Heritage of the Emilia-Romagna Regional Council, which will publish them as part of its own “Materials and Research” series, along with a range of objects inspired by a Renaissance fabric from the Gandini Collection, produced by the Davide Montanaro Studio of Industrial Design in Milan as part of the project Nutrire l’arte, in turn linked to Expo 2015.

We believe both this latter aspect and the exhibition project featuring the works of Marina Gasparini and the ensuing workshop provide a concrete demonstration of how a collection of antique fabrics may still arouse the creativity of artists and designers, thus stimulating a museum such as ours to seek out ever new opportunities for dialogue with the contemporary dimension.

Francesca Piccinini

Director Museo Civico d’Arte in Modena

DOWNLOAD THE CATALOGUE OF THE EXHIBITION:

Atlas X 2014.

Installazione al Museo Civico di Modena Sala Gandini. 46 elementi di filo di cotone dimensioni variabili . Foto Rolando Paolo Guerzoni Modena

photos by Rolando Paolo Guerzoni, Modena

PAROLE, OGGETTI, FILI: UNA LETTURA FILOSOFICA DEL LAVORO ARTISTICO DI MARINA GASPARINI

Francesca Rigotti

All’inizio era il filo, era il filo della ragione o lògos, il filo del pensiero, il filo del discorso; fili immaginari, metaforici. Ma anche un altro filo stava all’inizio, il filo-seme-sperma (questo vuol dire sperma in greco antico), che è poi il filo della vita al suo primo germogliare. I fili filati e articolati danno luogo, srotolandosi e arrotolandosi come serpi, alle parole; e le parole messe una dopo l’altra danno luogo alla linea (da linum, il filo o la cordicella di lino). La linea e la parola insieme producono il testo, dal latino textum, con quella “x” messa lì bene in mezzo a sottolineare l’intreccio di frasi. Che cosa raccontano le parole e le frasi e le linee? Ci dicono del mondo materiale e delle idee immateriali. Parlano delle cose e degli oggetti; soprattutto degli oggetti, quelle cose solide che ti vengono gettate davanti (dal latino ob-jectum) e che ti impicciano e che ti ingombrano e con le quali devi fare i conti.

Le parole di Marina Gasparini sono di un tipo particolare: alcune sono fatte di filo, perfettamente in linea con quanto abbiamo detto; altre stanno sugli oggetti, intorno agli oggetti, dentro e fuori gli oggetti. Altre ancora sono semplicemente esse stesse fili, fili morbidi che passano attraverso i forellini dei recipienti di ceramica, decorando la materia bianca come la pagina di carta. Le parole stanno sugli oggetti, intorno agli oggetti e raccontano pro-getti gettati in avanti nel futuro.

Ci sono scienze e discipline dell’inizio, come l’architettura, e storie dell’inizio, come tutte le storie di nascita. Nascita di bambini, nascita di idee. Ci sono storie che vedono protagonisti l’inizio, l’architettura, il filo: c’è una storia in particolare, la storia del labirinto, dove il primo architetto fa edificare un famoso palazzo che presenta un problema, la cui soluzione generale, collettiva, sociale sarà offerta da un filo. Filo = mítos o spérma dunque, in greco antico. Mítos come filo, dove mythos invece è la parola. Il filo della vita. Il filo dei pensieri e il filo della storia. Il filo della memoria e il filo del ragionamento. Trovare il filo, seguire il filo, perdere il filo. Fare il filo alle ragazze. La nostra vita è appesa a un filo. Il filo di lino è la linea, già lo sappiamo, e la linea è la traccia della scrittura («on-line») e dall’intreccio di linee nascono la tela («web») e la rete «net». Guardate il lavoro di Marina Gasparini, guardatelo bene: non vedete la compenetrazione delle capacità del computer con attività antiche, filare, tessere, cucire, passare fili? E lì che si condensa l’esperienza del pensiero creatore e creativo, dell’azione nei suoi aspetti produttivi. In principio c’era allora la textura ma anche la tectura, la tectura prima, l’ar-chi-tectura. Tekton è l’artefice (si pensi a techne), è l’artigiano, è chi fa, fabbrica e produce, chi traccia il disegno dell’edificio, che ne ha la prima idea e intuizione dunque, e poi presiede alla sua costruzione. Come negli interni di ghiaccio di non posso + esserci x te di Marina Gasparini, silenziosi, inquie-tanti e iniziali e progettuali, archi-tecturali.C’era anche un architetto che era pure il primo architetto, un archi-architet-to. Si chiamava Dedalo. E c’era un mito che è il primo e il più antico, il più arcaico mito della mitologia greca, il mito del labirinto costruito da Dedalo. C’è un filo che esce dalla ghiandola dell’addome del ragno (l’aragna, diceva Petrarca e aveva ragione, perché il ragno è un animale femminile) e produce reti e tele bellissime, ma aeree, effimere, inconsistenti. Il filo di bava trasparente che esce dal ventre dell’animale è esile e fragile e poco adatto a rappresentare la stabilità e la consistenza del testo/tessuto. Più adeguata invece, la produzione del filo a mano e poi la lavorazione dei fili intrecciati in vari modi: con l’ago, al telaio, all’uncinetto, ai ferri, a formare – nei lavori di Marina Gasparini – parole cucite, a rappresentare attività creative. Creative? Creazione? Creatività? Anche la creatività, variante umana e «secolarizzata» della creazione, è legata all’inizio, al momento della nascita dell’idea, dell’invenzione, della scoperta. Scientifica come artistica, ma qui ci soffermeremo sulla creazione artistica dato il contesto della mostra. L’idea di creatività nasce nel Rinascimento, esplode nella cultura illuministica e si definisce nell’accezione odierna nell’Ottocento, fino al culto idolatrico che le viene oggi tributato. Molte cose si porebbero dire sulla creatività, ma la più rilevante nel contesto delle opere di Marina Gasparini mi sembra quella relativa al fatto che la creatività stessa è arché, inizio, principio nel senso già definito, ed è filo: è un processo che contempla l’intero svolgimento di sé stesso e non soltanto la prerogativa di un solo istante iniziale da considerare separatamente dal resto; è filo perché è un processo che si dipana come da una matassa o da un gomi-tolo, affine in ciò al gomitolo che Arianna porge a Téseo per farlo uscire dal labirinto. L’immagine del filo è onnipresente, dall’Antico Testamento all’Iliade e all’Odissea, come alla moderna epoca dei computer. Considerati la costanza e il senso dell’esperienza del filare e dell’intrecciar fili, non ci si deve stupire del fatto che anche il pensiero filosofico ne abbia tratto ispirazione per cercare di comprendere ed esprimere l’attività creatrice e creativa del riflettere e del filosofare: anzi, tutta l’attività del pensiero creatore potrebbe essere definita come attività di filare e intrecciare: afferrare fili di pensiero e bandoli della matassa di idee altrui, filare da sé fili autonomi e con tutti tessere e annodare e intrecciare una nuova e originale rete di riflessioni. La storia del pensiero creatore dell’inizio come filo, nonché dell’attività creatrice inizia col mito di Arianna, del quale si è detto, e continua non a caso col mito di Arachne nar-rato nelle Metamorfosi di Ovidio e con quello di Ananke, la necessità. Si con-sideri la preponderante presenza femminile nella storia della creatività, legata a tre personaggi dai nomi così simili: Ananke, Arachne, Ariadne. Come se le tre figure volessero unire le proprie forze per ribadire di fronte agli uomini il medesimo principio: anche noi donne siamo creative, di figli e di idee siamo creative, non crediate di poterci relegare nel regno della riproduzione per tenervi quello della produzione, non arrogatevi il monopolio della creatività astratta, di idee e pensieri, non pensate che esso sia addirittura superiore alla nostra creatività che è duplice, perché è di carne e di sangue ed è di pensieri e di idee.

Torniamo al filo, filo della creatività e della mobilità, agile e flessibile, duttile, malleabile, morbido, aereo e libero, non costretto ancora nella cornice rigida del telaio, della cimosa o in ogni caso della forma obbligata: come non vederlo all’opera nel mobilio filato da Marina Gasparini, nello spaesaggio in cui i mobili sono disegnati sul muro dal filo di cotone nero che corre e scorre e avanza e si arrotola e si ritorce e torna indietro e intanto disegna un mobile, anzi lo scrive in corsivo, senza staccare la punta della matita dal foglio né il filo dal muro. E come non vedere la sua utilizzabilità ancora oggi, soprattutto oggi, quando rigidi e congelati modelli di pensiero e di azione incontrano potenti limiti e sembrano giunti ai loro confini, in ecologia, economia, tecnica, cultura, scienza, società e persino nella vita privata? Ci aiuterà forse il filo a vincere la sfida di un pensiero creativo libero e fluttuante, per un’azione dinamica, morbida, agile e colorata, da svolgere come il filo di una matassa per comporre, in astratto e in concreto, opere come quelle di Marina Gasparini?

WORDS, OBJECTS, THREADS: A PHILOSOPHICAL READING of Marina Gasparini’s artwork

Francesca Rigotti

In the beginning, there was the thread, the thread of reason, or logos, the thread of thought, of discussion; imaginary, metaphorical threads. But there was also another thread in the beginning, the thread-seed-sperm (this is what sperma means in ancient Greek), which is also the thread of life in its earliest budding. Unfurling and curling up, like snakes, threads are spun and articulated, giving rise to words; words placed one after the other give rise to the line (from linum, the linen thread or yarn). The line and the word together produce text, from the Latin textum, with that ‘x’ sitting squarely in the middle to underline the intertwining of sentences. Just what do words and sentences and lines tell us? They tell us of the material world and of immaterial ideas. They speak to us of things and objects – particularly objects, those solid things that are thrown in front of you (from the Latin ob-jectum) and which get in your way and clutter you up and which you have to come to terms with.

Marina Gasparini’s words are ones of a particular kind: some are made of thread, perfectly in line with what we have said; others are on objects, around objects, or inside or outside objects. Yet others are simply threads themselves, soft threads passing through the little holes of ceramic containers, decorating the white of paper pages. Words lie on objects, around objects, also telling of projects cast forward into the future.There are sciences and discipline of the beginning, like architecture, and stories of the beginning, like all the stories of birth. The birth of children, and of ideas. There are stories that feature the beginning as the protagonist, like architecture, and like thread: there’s one story in particular, the story of a labyrinth, in which the first architect has a famous building built which presents a problem, to which the general, collective, social solution will be provided by a thread. Hence, thread = mítos or spérma, in Ancient Greek. Mítos like thread, while mythos instead is the word. The thread of life. The thread of thoughts and the thread of history. The thread of memory and the thread of reasoning. Finding the thread, following the thread, losing the thread. The thread of a screw or a bolt. Our lives hanging by a thread. The thread of linen is the line, as mentioned before, and the line is the trace of writing (like an online discussion) and the intertwining of lines gives rise to a web and net. Take a good look at Marina Gasparini’s work: can you not see the compenetration of computer capacities with physical activities, like spinning, weaving, sewing and threading? It’s there that the experience of creative thought, of the action’s productive aspects, comes to a head.

In the beginning, there was textura but also tectura, in fact tectura first of all, as in archi-tectura. Tekton is artifice (think of techne); it’s the artisan, it’s he that makes, fabricates and produces, he that traces the outline of the building, and thus he who has the first idea and intuition, before presiding over its construction. Like in the icy interiors of non posso + esserci x te by Marina Gasparini: silent, unsettling, initial and projectual, i.e. archi-tectural.There was also an architect who was no less than the first architect, an ar-chi-architect. His name was Daedalus. And there was a myth which was the first and most ancient, the most archaic myth of all of Greek mythology: the myth of the labyrinth built by Daedalus.

There’s a thread that comes out of the gland on the abdomen of the spider (the “she-spider”, as Petrarch said and he was right, because the spider is indeed a feminine animal) and produces beautiful nets and webs, yet almost airborne, ephemeral and inconsistent. The transparent thread that pours forth from the belly of the animal is light and fragile and unsuited to representing the stability and consistency of texts/textiles. Instead it is more fitting to think of the manual production of thread and the working of threads bound together in various ways: with the loom, the crochet needle, knitting needles, to form – in Marina Gasparini’s works – sewn words, representing creative activities. Creative? Creation? Creativity? Also creativity, the human and “secularised” variant of creation, is linked to the beginning, to the moment of the birth of the idea, of invention, of the discovery. It may be scientific or artistic, but here we shall focus on artistic creation, given the exhibition context. The idea of creativity dates back to the Renaissance; it was then to explode in the culture of the enlightenment and is defined in the modern-day acceptation only in the 19th century, right up to the idolatry cult that today is bestowed upon it. Many things could be said on creativity, but the most relevant one in the context of the works by Marina Gasparini would appear to be that relating to the fact that creativity itself is arché, a beginning, the starting point, in the sense of being already defined, and it’s s thread: a process that contemplates its own entire development and not just the prerogative of a single initial instant to be considered separately from the rest; it’s a thread because it’s a process that unfurls as if from a tangle or a ball, hence like the ball of thread that Ariadne gives to Teseo in order to lead him out of the labyrinth.

The image of the thread is everywhere we turn, from the Old Testament to the Iliad and the Odyssey, right up to the modern age of computers. Given the constancy and the sense of the experience of threading and weaving threads, it should come as no surprise that also philosophical thought has drawn on it for inspiration in order to try to understand and express the act of creation and of creativity in reflecting and philosophising. As a matter of fact, all the activity of creative thought could be defined as the activity of threading and weaving: grabbing onto threads of thought and finding the thread-ends of others’ ideas, spinning one’s own autonomous threads, and then all together weaving and knotting and intertwining a new and original network of reflections. The history of creative thought as a beginning like a thread, not to mention creative activity, starts with the myth of Ariadne, as mentioned above, and not by chance continues with the myth of Arachne as narrated in Ovid’s Metamorphosis, and with that of Ananke: “necessity”. Just consider the preponderant female presence in the history of creativity, linked to three characters with such similar names: Ananke, Arachne and Ariadne. As if the three figures wanted to join forces to underline the same principle before men: we women are creative too; we create both children and ideas, but don’t think you can just relegate us to the realm of reproduction so as to keep that of production all to yourselves, don’t demand the monopoly of abstract creativity, of ideas and thoughts, and don’t think that yours is in any way superior to our two-fold creativity, for ours is both one of flesh and blood as well as of thoughts and ideas.

Let us return to the thread, the thread of creativity and mobility, agile and flexible, ductile, malleable, soft, airy and free, not yet bound by the taut frame of the loom, of the selvage or at any rate of the imposed shape. We cannot but notice this at work in Marina Gasparini’s threaded furnishings, in the crooked landscape against which the furniture is drawn onto the wall with the thread of black cotton that charges ever onwards, rolling up and twisting back upon itself as it outlines a piece of furniture, or rather, it writes it onto the wall without ever lifting the tip. And how could we overlook its usabili-ty even now, especially now, when rigidly trenched models of thought and action come up against powerful limits and seem to have reached the end of the line, in ecology, economics, technology, culture, science, society and even in our own private lives? Will it perhaps be the thread that helps us to win the challenge of a free and floating creative thought, of a dynamic, soft, agile and colourful action, to be deployed like the thread of a skein to put together – both in abstract and concrete terms – works like those by Marina Gasparini?

THE LIST OF PLANTS DOWNLOADS

Piante in fila vista generale 3 DISEGNO

UN GIARDINO SOSPESO

Marco Pierini

Dall’arte / della lana e della seta/

l’Italia / ebbe ricchezza lustro /civiltà

Le parole in esergo si leggono dipinte sulla cartella sovrastante una delle porte d’ingresso alla sala del Museo Civico di Modena che nel 1886 Luigi Alberto Gandini fece apparecchiare e decorare perché accogliesse l’ingente patrimonio di frammenti tessili negli anni raccolto e allora donato alla collettività. Il medesimo monito tornito dall’illuminato collezionista con moderata e sincera retorica risorgimentale può essere assunto, stemperati gli accenti patriottici, come viatico alla lettura dell’intervento di Marina Gasparini, il cui titolo Il denaro è un bene comune (ciascuna delle lettere che compongono la frase, ricamata, trova spazio, quasi mimetizzandosi, nelle vetrine assieme agli antichi tessuti) esplicita fin da subito uno stretto legame tra arte tessile ed economia che avrebbe certamente riscosso l’approvazione del conte Gandini. Una visione dell’economia quasi domestica, che rivendica appunto la sua radice dall’etimo greco oikos (casa, ma anche patrimonio di famiglia) e ristabilisce la sua inscindibile connessione con il lavoro, la manualità, la trasformazione della materia, il territorio.Dalle catene di ferro che attraversano la sala sotto le volte pendono, filate in cotone, piante di numerose varietà, restituite nel loro aspetto esemplare come appaiono miniate nei codici erbari del medioevo e del rinascimento, oppure cavate dal cinquecentesco hortus siccus di Ulisse Aldrovandi e miracolosamente restituite, se non alla vita, alla morbidezza e alla misura delle loro forme originali.

Da ogni specie si estrae un pigmento, e di questo colore il corrispettivo ‘disegno tessile’ integralmente s’intride, si tinge, a simboleggiare in maniera quasi araldica il frutto delle proprie fibre: blu l’Indigofera tinctoria, rosso il Carthamus tinctorius, arancione il più comune melograno, verde l’Iris pseudacorus.

Le piante sospese, nel loro aspetto fantasmatico che consente all’occhio di attraversare la sala intera senza incontrare ostacoli – sguardo che sembra alludere al taglio diacronico della raccolta, ricca di quasi un millennio di storia del tessuto – entrano in mutuo colloquio coi lacerti tessili custoditi all’interno delle vetrine, le cui preziose qualità cromatiche tutto debbono ai pigmenti estratti dalle foglie e dai fusti. Con tatto, l’installazione di Marina Gasparini pone il visitatore di fronte a un processo estremamente complesso che parte dall’agricoltura, attraversa tutte le fasi della lavorazione della materia, poi la creazione artistica, il commercio, infine la salvaguardia, la conoscenza, l’educazione: economia, si potrebbe dire con una sola parola. Economia che è essenzialmente sistema di relazioni, interdipendenza, mutuo scambio, condizioni, azioni e rapporti che il filo simbolicamente racchiude in sé da sempre, come in altra parte di questo libro ci racconta Francesca Rigotti.

L’etereo giardino dell’artista non riverbera soltanto la classificazione scientifica delle piante e il loro utilizzo in campo artigianale e industriale, ma evoca immediatamente anche la presenza dominante del regno vegetale nell’iconografia dell’arte tessile a ogni latitudine e in ogni tempo. Natura che, in quanto antropizzata, non può sottrarsi infine dal divenire paesaggio, elemento costitutivo della nostra vita quotidiana prima ancora che schermo su cui posare lo sguardo. A questo aspetto è maggiormente rivolto il grande libro di stoffa che completa l’installazione, nelle cui pagine le immagini si accompagnano a frasi di celebri economisti come Bernardo Davanzati e Stuart Mill. Se ne estrae, a guisa di explicit, una sentenza di François Quesnay ancora attualissima, sebbene risalente al 1768, e che oggi dovremmo avere la forza e l’intelligenza di estendere dal mondo della natura a quello dell’arte e del patrimonio culturale: L’aria che respiriamo, l’acqua che attingiamo al torrente e tutti gli altri beni o ricchezze sovrabbondanti e comuni a tutti gli uomini non sono commerciabili: sono beni e non ricchezze.

A HANGING GARDEN

Marco Pierini

From the art / of wool and silk/

Italy / gained wealth, lustre /and civilisation

The words of the epigraph are painted on a panel above one of the entrances to the room in the Museo Civico in Modena which, in 1886, Luigi Alberto Gandini had prepared and decorated in order to house his huge collection of textile fragments, which over the years he had compiled and then donated to the public. The same reminder worded by the enlightened collector, with his moderate yet sincere Risorgimento rhetoric, may be taken – patriotic fer-vour aside – as a viaticum for an interpretation of Marina Gasparini’s intervention, the title of which Il denaro è un bene comune (Money is a common good, of which each letter making up the sentence is embroidered, finding its own space – or almost camouflaging – amidst the ancient fabrics), made explicit right from the start through the close link between textile art and economics which would undoubtedly have met with the approval of Count Gandini. Such a domestic vision of the economy, claiming back its roots from the Greek oikos (home, but also family heritage) and restating its innate connection with work, manual labour, the transformation of materials, of matter and territory.Cotton threads hang from the iron chains suspended across the room, beneath the vaults, depicting numerous varieties of plants, their exemplary aspect reflecting the miniatures to be found in medieval and renaissance herbaria, or taken from the 16th-century hortussiccus by Ulisse Aldrovandi and miraculously restored, if not to life, to the softness and measure of their original forms. From every species, a pigment may be extracted, and the correspon-ding ‘textile design’ is then imbibed, dyed with this colour, symbolising the fruit of its fibres in almost heraldic terms: the blue of the indigofera tinctoria, the red of the carthamus tinctorius, the orange of the more common pome-granate, and the green of the iris pseudacorus.

In their ghostly appearance, which allows the eye to cross the entire room without coming up against obstacles – a gaze which seems to allude to the diachronic cut of the collection itself, with almost a complete millennium of textile history – the hanging plants converse with the fabric samples lying inside the vitrines, of which the precious chromatic qualities are created thanks to the pigments extracted from the leaves and stems of those plants. Marina Gasparini’s installation tactfully places the visitor before an extremely complex process which starts out from agriculture, crossing all the working stages of materials, right up to the stage of artistic creation, trade, and lastly the fabrics’ safeguarding, study and educational use: in a word, economics.Economics being essentially a system of relationships, interdependence, mutual exchange, conditions and actions that the thread has always symbolically summed up, as explained elsewhere in this publication by Francesca Rigotti.

The artist’s ethereal garden does not only reflect the scientific classification of the plants and their use in the field of craft and industry, but also immediately evokes the dominant presence of the vegetable kingdom in the iconography of textile art throughout the world and throughout the ages. A form of nature which, being humanised, ultimately cannot deny its becoming landscape, a key element of our everyday lives, and a backdrop to many of the scenes on which we cast our gaze. This aspect is addressed more clearly by the great fabric book which completes the installation, the pages of which feature images along with quotes from renowned economists like Bernardo Davanzati and Stuart Mill. By way of example, we might pick out one by François Quesnay which is still highly relevant even though it dates back to 1768, and which today we should have the strength and intelligence to extend from the world of nature to that of art and our cultural heritage: The air we breathe, the water we draw from the river and all the other overa-bundant goods or riches common to all men are not saleable: hence they are common goods and not riches.

Rubia (rubia peregrina) cm 83X 84., cotton thread.

Marco Rambaldi Potographer, Bologna

Installation at Civic Art Museum of Modena, the Gandini hall.

Cotynus Cogyria cm 109×60, cotton thread.

Marco Rambaldi Photographer, Bologna